Welcome to part two of How My Chemo Treatment Led To An Eating Disorder! WOOHOO!! If you haven’t already read part one, do that here. (Otherwise, things might not make sense.)

To recap where I left off last time:

“The final nail in the coffin, so to speak, was one wayward comment from one of my oncologists: “Your weight has been steadily increasing for weeks now, and it’s getting difficult to do your spinal taps. Maybe you should just cut back a bit on eating.”

After hearing these words, I choked down my tears and nodded, feeling dumbfounded and ashamed of my entire being. My mom was livid. She was already concerned with how little I had been able to eat over the previous two years. She knew this doctor was not taking my medical conditions or the fact that I had been taking high doses of prednisone for over a year, into consideration.

But regardless, the damage had been done. And if I could pinpoint the exact moment when I decided to stop eating altogether, it was that moment in my treatment clinic when a doctor, who was supposed to know what was best for my body, told me to “cut back” on food. “

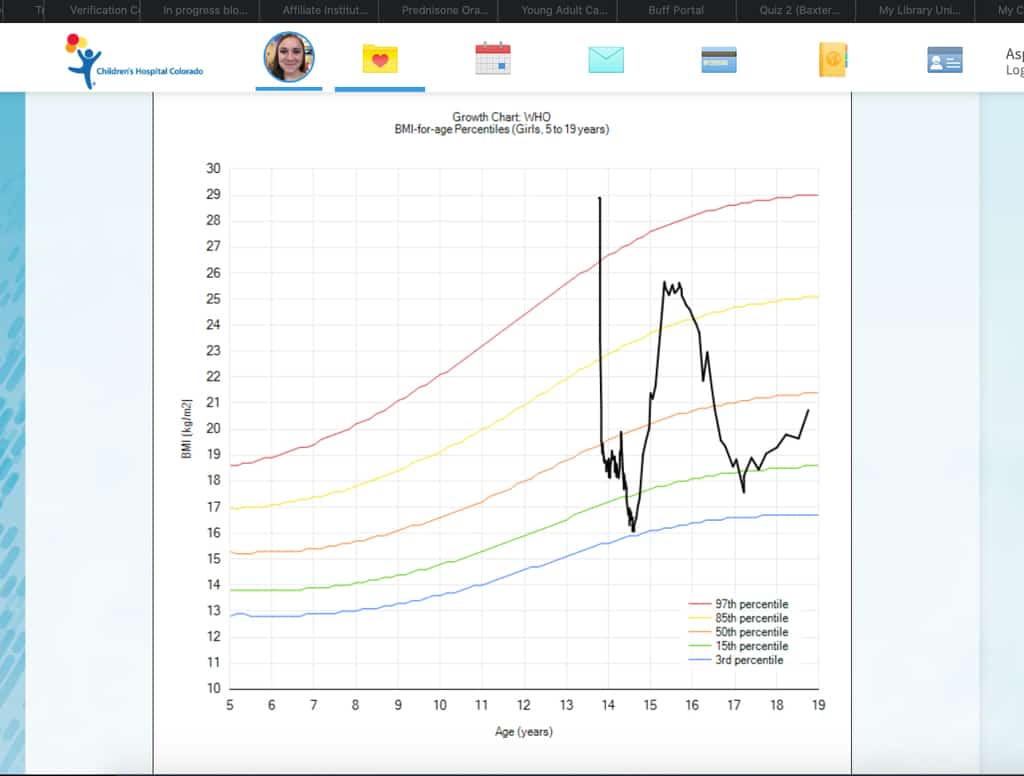

Above is an image of the chart (found in my online medical portal) that shows how my weight changed from 2013 to 2018. The black line begins when they first started taking my weight a few months into my treatment. This was soon after I had gained weight from the first round of high-dose steroids. It’s pretty high as you can tell. You can see how much the line fluctuates over the next few years. The second-lowest point is when I was around the time I was confronted about my eating disorder.

Near the end of my two and a half year treatment, my ability to cope had evaporated (I know, it’s a big shocker). I was 1000% done. Done with how sick I felt, how limited I was, how out of control my life had been, how much I had lost, and with my entire appearance. I was deeply ashamed and embarrassed by how overweight I was. I needed something, anything, that made me feel like I was in control. I didn’t understand that my weight was completely drug-related and had nothing to do with my diet or activity levels. My doctor’s comment was all the confirmation I needed.

I became determined to do something about my weight. All my 14-year-old self could conclude was that people lost weight by dieting and exercise. Did I know what a healthy diet looked like? No. Did I know what a healthy exercise for my body would be, given that it had been thoroughly damaged and was still going through an intensive chemotherapy regimen? No.

So I used the only logic I had at my disposal and came to a few of my own conclusions.

I had already spent over a year barely eating anything due to nausea, so choosing to forsake my daily bowl of cereal I had worked up to stomaching didn’t seem that drastic to me.

Food truly didn’t seem that important.

At this point, I had already started to force myself to run. I had started ever-so-slowly, increasing my time and distance as I fought against the abhorrent state of my body. I was initially running to feel strong, so running even MORE to potentially help me lose weight felt like a bonus.

Pushing myself to eat less and run more became my mantra. After 2 months, it became my worst habit. After 6 months, it became my lifestyle. My only priorities on any given day were enduring that I ran enough and avoiding situations where people would want me to eat.

There were so many intense, unprocessed emotions from the trauma of my treatment that I needed to escape—There was so much that had been so horribly out of control for so long. A huge part of me desperately needed to feel strong and not sick. I badly needed to feel like I had control over some of my body’s abilities and how it looked. And there was also a part of me (an understandable part) that wanted to punish my body for the pain it had caused me, and I knew depriving it of food was a way of doing that.

By running and not eating, I felt like I was killing so many birds with one stone—It felt like I was regaining some of the control I had been lacking for so many years.

At first, when I started running and eating next-to-nothing, my weight didn’t budge. A few months passed like this, but I didn’t stop. Then my treatment ended, I got away from the god-awful prednisone, and my body slowly started to change. As soon as I saw this progress, I believed that my efforts were just beginning to pay off, and I needed to up the intensity. I started running twice a day and eating one piece of fruit a day. The weight SLOWLY came off.

People kept telling me I looked so good and that I had lost weight. (Hey, it’s a miracle what your body can do when it’s not being pumped full of toxic chemicals). Since I didn’t understand that it was being OFF of the prednisone that was allowing me to lose weight, the compliments just served as reinforcement for my behaviors.

I truly thought my hard work and starvation was just starting to pay off. This led to a twisted sense of pride about what I was doing. During that time, I was acting out of a desire to feel that sense of accomplishment, but I was mostly acting out of fear.

You see, I believed—with every ounce of my being—that the only thing keeping the weight I lost from coming back was my routine. Embedded into my VERY SOUL was an irrational fear and belief that if I didn’t keep up my routine, I would go backward and gain weight again. That thought was something I couldn’t stand.

I was also becoming the star runner on my high school cross country team at this time. How hard I was able to race after everything I had been through was considered a big inspiration to my community. This was the first time people actively began to talk about me being an inspiration to them, and that admiration was deeply tied to me being such a great athlete. This made me even MORE proud of my behaviors. I could run crazy amounts and not even eat. What an accomplishment.

To top it all off, I looked great. I was finally back to my normal weight of 110, felt strong, and looked athletic. Finally looking like myself again after years of feeling like a mutant. It was a body I had worked and starved for. I felt strong and capable because I was able to run so often and so far. I had managed to get away from the places of my life that felt the worst. The place where I felt like I had no control, felt weak and sick and despised how I looked. I felt free. But I was the farthest thing from free. I had taken my own control away. Because even though I was finally where I wanted to be, and I couldn’t stop or even slow down.

I progressed to the point that I was running ten miles a day, all in one run, and eating only an apple. Or nothing at all. Close to two more months passed. My weight inched down to the 90lb mark.

I was pushed by my desire to feel strong and capable, to have control over my body, to look differently, to punish myself, and to literally and figuratively run from that trauma I had been through.

My chemotherapy history of not being able to eat on chemo, not caring about food, of hating myself and my body, of getting used to the idea that my body didn’t do anything “normal” and needed EXTREME measures to cooperate, made it worse.

It was the perfect storm.

Running was the only thing that made me feel like I was alive, which wasn’t bad in itself. I was just running too much, not giving myself any rest, and not eating.

After going without food for a while, you don’t feel hungry anymore. Chemo had gotten me to this point before I started running. And even though I was depriving my body of food months later, I was still able to run just as much as I wanted. This left me feeling like I had no physical or mental drive to eat anything. I didn’t feel hungry, and I didn’t care if I ate.

I didn’t even realize what I was doing until I was trapped in my patterned behavior and unwilling and unable to stop. Starving myself became something that felt so right to me, and so necessary, that I couldn’t force myself to quit. I was in the deep end of a deadly addiction.

At some point, I did understand that I was killing myself, but I couldn’t bring myself to care. I remember actually smiling about it and thinking “good”.

For or over a year, no one fully understood what I was doing. My family had their suspicions but were all too worried about upsetting me to stage a confrontation. My mental state was so fragile, no one wanted to make things worse. They didn’t know what to believe because I would lie all the time about how much I was eating.

“Between the duration of most cancer treatment regimens, the immense loss of control and physical discomforts or limitations in our patients lives, and how treatment often affects their physical appearance and weight, chemotherapy creates the perfect storm for the development of eating disorders”

I remember one of my oncologists saying this to me months AFTER they found out I was full-blown anorexic. They had suspected for a while. My bi-weekly check-ups (to ensure my cancer wasn’t recurring) had shown a trend of steadily declining weight and decreasing heart rate.

At that point, I didn’t even fully understand what an eating disorder was. I didn’t even fully understand what I had been doing to myself or even all the reasons why.

None of that mattered. My body was at its own breaking point.

At one particular bi-weekly check-up, my doctors finally confirmed what they had been silently suspecting for months: that I had anorexia. My weight was below 90lbs, and my resting heart-rate was at 34 beats a minute. Because I was at risk for heart problems due to high-dose chemo and steroids, my heart was considered to be in a critical condition. My oncologists classified me as someone with an exceptionally high risk of having a heart attack at any time. I was told that just walking around could trigger one.

My doctors planned to hospitalize me in an anorexia treatment program for months, where tubes would be shoved down my throat if I didn’t eat. I was in no place to handle that mentally or emotionally. One more hospital stays where I would be forced to do things I felt like I couldn’t handle would have been the thing to break me.

When my doctors declared this as the plan, I refused and fled. My medical team eventually corralled me in another isolated room, but I was hysterical and feeling deeply ashamed.

After a few minutes of panicking and saying “You can’t make me go!” over and over, I just broke down into tears. This was when a nurse told me that my mom had negotiated to give me two weeks to show good progress. If I got my weight up, showed an increase in heart rate, within the next two weeks, they wouldn’t hospitalize me.

This meant I had to start eating a significant amount of food and completely refraining from any exercise for months. This meant going without my two biggest coping mechanisms and comforts. This meant I had to find some way to do the things I felt with every ounce of my being were physically impossible to do.

My vitals would have to be taken a couple of times every day during those two weeks. If I showed any signs of losing more weight or my heart-rate going down.

I yelled at everyone, saying that I would rather die. That I didn’t care if I died.

It was like they were asking me to kill the person I loved most in the world. It felt physically and mentally impossible on every level.

There was no part of me that felt like I could do what they wanted. I couldn’t stand the idea of losing the control I had created for myself, and a huge part of me just wanted to die.

A life or death choice. That’s what it came down to.

Given my medical history, this was a very familiar choice for me. The only difference was, this time, it was MY choice. Every other time something needed to be done to save my life (starting chemo, doing emergency surgery, continuing to do chemo when it was hell), I didn’t have a choice because someone made it for me.

This time, I refused to be forced into anything. No one could give me the will to live. In the end, no one could force me to eat. My family begging me wouldn’t matter. Even if I was forced into a hospital, I knew I could fight whatever they did until I died.

If I was going to live and do what it took to survive, it had to be MY choice.

When I realized that I ultimately had the power, I calmed down. The doctors took my vitals again after a while to try to see if I was even fit enough to go home. Since the results were consistent with the first set of vitals and not worse.

I was in that clinic most of the afternoon, talking to doctors, listening to my mom and boyfriend at the time cry, and beg me to keep going, dissociating from everything, and thinking.

I finally made the choice to live—the choice to go home, start eating, and do better. It was one of the most difficult choices I have ever made, and it was even harder to follow through on that choice.

Now, WHY I ultimately came to that conclusion, how I was able to turn things around without being hospitalized, how I dealt with all the difficulties of overcoming my eating disorder, and all the other nitty-gritty details, are stories for another time. More to come! I look forward to seeing you there! 🙂

Keep your eye on your inbox, or sign up for the newsletter if you haven’t!

Normality is a paved road; It’s comfortable to walk, but no flowers grow.

-Vincent Van Gogh

Latest posts by Aspen Heidekrueger (see all)

- How My Chemo Treatment Led To An Eating Disorder (PART 2) - November 16, 2020

- How My Chemo Treatment Led To An Eating Disorder - November 8, 2020

- Another Encouraging Word for Cancer Survivors (And Everyone Else) - October 25, 2020

These true life stories show you’re finally at a place where you can reach inside and unlock all those deepest feelings that accumulated during treatment and the long recovery period. Thanks for being vulnerable enough to put into writing the stories that will help the rest of us see a bit better what most of us will never truly understand. You have given us a clear picture of the inside, raw details. Thanks again.

You have really made this understandable for people who don’t know what it is to face an eating disorder. I wish you hadn’t had to go through this hell, but I’m proud of you for getting through it and talking about it.

I can’t even begin to imagine what you’ve been through, Aspen, but am so thankful that you are able to share your story. I know that you’ll help others that are battling with eating disorders and the aftermath of cancer treatments! Sending hugs, dear one!